He was handed over as a hostage by George Washington, spied on his captors and is credited by some as providing the key to the British conquest of Canada. Yet these days few in Canada or his native Scotland have heard of Robert Stobo.

Stobo was born in 1727 into a Glasgow merchant family. His father died in 1740 and two years later he sought his fortune across the Atlantic in Virginia. By 1747 he was running his own import/export business and looked set for a quiet but prosperous life in one of Britain’s oldest colonies..

But trouble was brewing in the Ohio Valley. The British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania had both been greedily eyeing the Ohio Valley for several years. They now claimed the areas as one of the fruits of 1748 Treaty of Aix la Chapelle with France. The French, however, remained keen to spread New France from the Great Lakes south via the valley to Louisiana on the Gulf of Mexico.

Virginia decided to raise an infantry regiment to enforce its claim. Command of this ragtag force eventually fell, through political influence, to an ambitious 22-year-old surveyor and land speculator called George Washington. Stobo, also through political influence, was appointed the force’s engineer. He had no military engineering training but the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie was a fellow Glaswegian and distant relation.

Washington and around 160 of his men soon located around 40 French and Canadiens in the disputed area. The future President took 110 men to the clearing where the men from New France were encamped. The Virginians’ musket volleys quickly decided the contest. What the Virginians considered a fair fight, the Canadiens branded an ambush. The leader of the men from New France, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, was killed; quite possibly by one of the dozen or so Indians attached to Washington’s force.

Washington decided to build a crude fortification, christened Fort Necessity, and await events. He sent 21 prisoners to Virginia. Travelling in the other direction to the prisoners on the forest trail was Captain Stobo with a wagon full of supplies, including a barrel of wine, and 15 more men.

Not long after Stobo arrived, so did a force of 600 French regulars, Canadiens and Indians under the command of Jumonville’s brother Francois. Fort Necessity’s defence works were inadequate and the trenches were quickly flooded by rain, which also soaked the Virginians’ gunpowder. After an exchange of fire, a surrender was agreed.

Washington agreed to hand over two hostages to guarantee the return of the 21 prisoners taken after Jumonville was killed. He also signed a surrender document which admitted that Jumonville had been murdered. Washington later claimed that this confession was due to a mis-translation of the surrender terms by one of his officers, a former Dutch Army officer called Jacob van Braam. As the word used was “l’assissinat”, Washington’s excuse lacks credibility.

Van Braam, perhaps not surprisingly, was one of the hostages. The second was the only other unmarried Virginian officer present, Stobo.

The surrender terms included a guarantee that the Virginians’ property would be stored until a wagon could be sent to collect it. Another provision promised safe passage for all of Washington’s men out of the disputed territory. As soon as the Virginians left the fortifications on 4th July 1754, the Indians swooped in to loot them. They also snatched more prisoners.

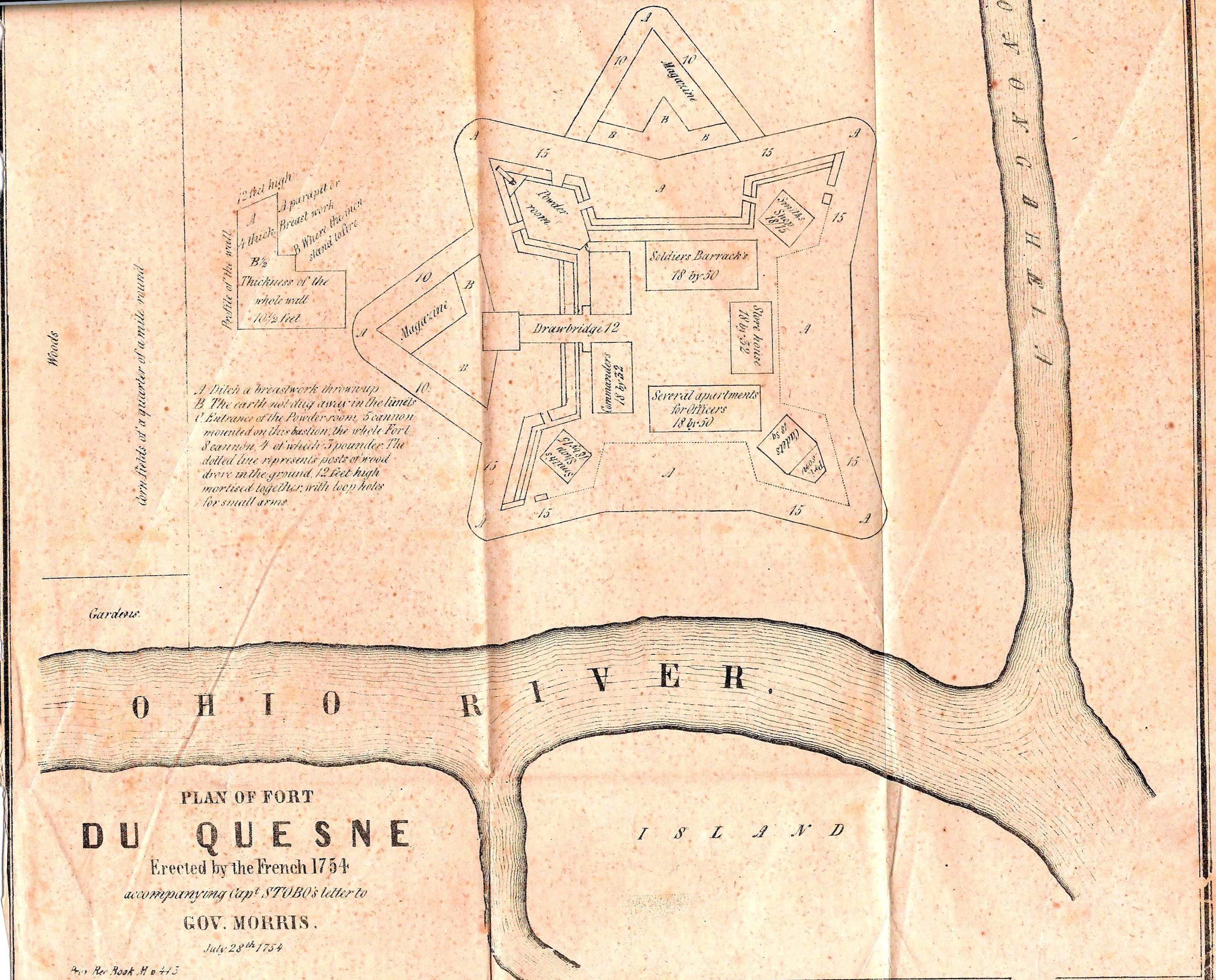

Stobo would later argue that as the surrender terms were broken, he was under no obligation to honour them either. Stobo and van Braam were taken to the key French base in the disputed area, Fort Duquesne. Stobo quickly drew a detailed plan of the fort and noted the garrison’s strength and routine.

A copy of Stobo's map of Fort Duquesne

A copy of Stobo's map of Fort Duquesne

Stobo managed to smuggle out two letters and the fortA copy of Stobo's map of Fort Duquesne plan via two friendly Indians who took them to the British. Unfortunately, copies were made. An English newspaper reported that a plan of the fort was in British hands. This news was picked up by French agents and Paris forwarded it to New France.

By this time van Braam and Stobo had been moved to the heart of New France at Quebec City. After some dithering Dinwiddie had decided not to return the 21 prisoners captured by Washington. Stobo was enjoying a very full social life despite his captive status. Relations cooled when word of the Fort Dusquesne plan reached Quebec, but without proof the authorities decided not to charge Stobo with spying.

Sadly for Stobo the proof was found when a British army sent to capture the fort was routed in July 1755. The captured baggage of slain Scottish Major General Edward Braddock contained the plan and one of Stobo’s letters. Stobo and van Braam were put on trial for their lives in October 1756. Van Braam was acquitted after a 19 day hearing but Stobo was sentenced to the guillotine. The authorities in Paris refused to confirm the death sentence but Stobo was jailed.

Stobo managed to escape twice, in May and July 1757, but was recaptured on both occasions. His third attempt was better organised, and luckier. Together with an officer from Rogers Rangers, Simon Stevens; a Scottish shipwright called William Clark; Clark’s wife and three children; another soldier, Elijah Benbo; and another English prisoner, Oliver Larkin, Stobo managed to creep away from the fortified walls of Quebec City into the dark night one night in May 1759. The escapees crammed themselves into a birch bark canoe and set off down the mighty St. Lawrence River which flowed past the city.

After four days the party met two Indians on a little island. They claimed to be French but one of the Indians smelled a rat and tried to raise the alarm. He was killed and the other Indian, possibly his wife, was murdered. Clark scalped the Indians for the £24 bounty per scalp offered by the authorities in New York. The Indians’ dog was killed and their tent looted.

The escapees then managed to capture a small boat carrying a small-time Canadien landowner and four of his men. The Canadiens were then forced to row the party down the St Lawrence.

Stobo then managed to lure the crew of another French vessel ashore and then used their boat to board a second, larger, one lying nearby. The second vessel carried Stobo and his party to British occupied territory.

The Glaswegian was sent back to Quebec City which was by then besieged by a British force commanded by Major General James Wolfe. The siege was not going well and it looked as though it would have to be abandoned. Stobo has been credited with telling Wolfe about the lightly defended path which led from the river up onto the Plains of Abraham outside the city walls. But when Quebec City surrendered after the British victory on the plains, Stobo was already on his way to join a British force making its way north from what is now New York State to capture Montreal.

Stobo was then ordered to carry important military dispatches to the British base at Halifax in what is now Nova Scotia. When his ship was intercepted by a French vessel he threw the dispatches and other incriminating documents overboard and succeeded in passing himself off an unimportant passenger. The French let him go. Then while crossing the Atlantic in 1760, Stobo was captured by the French again but was eventually ransomed for £125.

Stobo managed to have himself commissioned as an officer with the British 15th Foot but suffered a badly fractured skull in 1762 while fighting the Spanish in Cuba. He returned to duty with the 15th Foot the following year but was by now a habitual drunk. On the 19th June 1770 while stationed at Chatham in England he blew his brains out with a pistol.