Scottish Military Disasters

Forgotten War

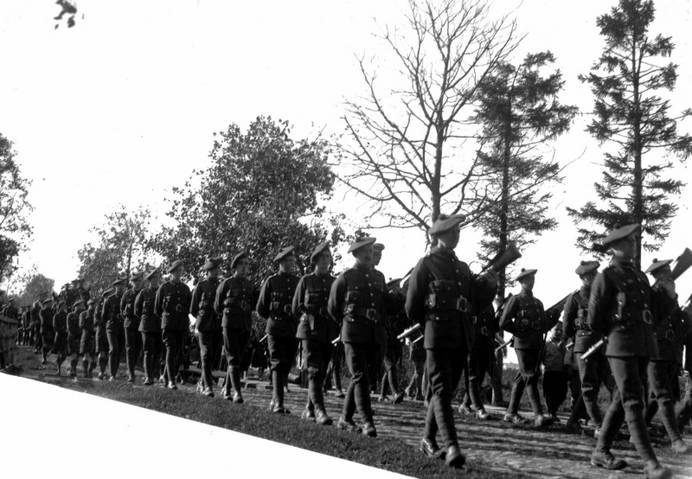

While the bulk of the British Army was cheering and waving tin hats in the air to celebrate the clock ticking over to the 11th hour of the 11th day in 1918 and the end of the First World War on the Western Front, soldiers from the Royal Scots were fighting for their lives in North Russia.

What was to become known as Armistice Day offered no respite from war for the men of the 2/10th Royal Scots; in fact the day saw them fighting one of their toughest battles against the Russian Red Army during fighting in the forest wilderness south of the key port of Archangel.

What made the Royal Scots’ war in North Russia all the more extraordinary was that the unit’s members had been deemed as physically unfit to fight on the Western Front. The battalion was made up of men in such poor physical condition, or so badly wounded, that they were deemed fit for nothing more strenuous than Garrison Duty in the British Isles. On November 11th 1918 they fought off a foe who outnumbered them five-to-one and who had already murdered captured members of the battalion.

The Royal Scots had been plucked from Garrison Duty in Ireland and sent to the North Russian port of Archangel to guard military supplies stockpiled there for use against the Germans on the Eastern Front. The seizure of power in Russia by the Bolsheviks in November 1917 had resulted in the country pulling out of the war in March of the following year. This left the supplies vulnerable to seizure by German troops operating in Finland. There were also fears the Germans would seize Archangel and the port of Murmansk further north and turn them into submarine bases. In addition there British were keen to support anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia.

Before the battalion left Ireland the most physically decrepit men were weeded out and replaced by slightly fitter men from other garrison units serving in the country. This brought a number of Englishmen into the battalion, but at heart it remained Scottish. The battalion had one thing going for it. The officers were all veterans of the Western Front. They had been sent to Ireland for a “rest” from frontline service. Efforts were also made to add some experienced sergeants to the battalion.

Chasing the Red Army

By the time the Royal Scots arrived at Archangel in August 1918 the Bolsheviks had been kicked out of the port by pro-Allied Russians. But the Red Army had taken many of the military supplies from the docks with them when they retreated south into the woodland wilderness. The British decided to push south into the forested interior after the Bolsheviks. The only practical transportation routes were the railway lines south from Archangel and Murmansk or the wide meandering rivers that flowed from the vast forested interior of Northern Russia to the White Sea. The bulk of the Royal Scots were sent 200 miles up the River Dvina on barges. The forest and river scenery were spectacular. But British hopes that villagers would join them in fighting the Bolsheviks were not fulfilled. The local people had no interest in fighting for anyone and only wanted left alone by both sides.

The British were not alone in Northern Russia. Several Allied nations had sent troops, including the Australians, the Americans, the French and the Serbs. A group of Russian-speaking Poles were also part of the expeditionary force. The Canadians were the pick of the artillery reinforcement depots in Britain and were an elite unit. The Allied troops, including th e Royal Scots, were armed with Russian Mosin-Nagant rifles. This standardised ammunition supplies.

e Royal Scots, were armed with Russian Mosin-Nagant rifles. This standardised ammunition supplies.

The three companies of Royal Scots sent up the Dvina joined a small force of British Royal Marines, Russian scouts, Poles and the crew of a British gunboat. The force had already clashed with the Bolsheviks and been forced to retreat. Once ashore the Royal Scots helped occupy several villages along the river. The villages had been abandoned by the Bolsheviks who were retreating until they got the measure of the new arrivals.

The first big operation for the Royal Scots was a march through the forest to surprise the Bolsheviks occupying the village of Chamova. The march was a nightmare. The five foot wide track leading from the river into the forest quickly petered out. The men found themselves wading through water that was mostly knee deep. To top it all, when the Royal Scots finally emerged from the forest at Chamova the Bolsheviks retreated.

But the force was to lose three men at Chamova when they mistook a Bolshevik gunboat for an Allied supply boat. When the men went unarmed to collect the supplies they were hacked to pieces with axes.

Following the capture of Chamova, the Royal Scots embarked on yet another flanking march through the forest. This time their target was the village of Pless. The going was even worse than it had been on the march to Chamova. The soldiers found themselves ploughing through a quagmire that was often knee-deep and seldom less than ankle deep. It later emerged that the Polish interpreters had refused to believe the column’s local guide that the way to Pless was blocked by a marsh. The Royal Scots ran out of food and were sustained on the second day of the march by a mouthful of tea for breakfast and whatever berries they could snatch from bushes as they passed them. Many of the soldiers only kept moving because their officers warned they’d be left to die in the forest if they stopped. When the Royal Scots arrived at Pless three days after setting out they found the Bolsheviks had slipped away again. The bad food and exhausting march meant that the soldiers needed two days rest at Pless before they could go any further.

The Royal Scots were ordered to fortify the next stop on their southward journey. Tuglas was a settlement of 200 log houses. Trenches were impossible because the water table was only one foot down and they flooded. So the Royal Scots improvised blockhouses by dismantling village steambaths piece by piece and re-assembling them in locations with good fields of fire to defend the settlement. The former bathhouses were ringed with a second wall and sand piled up between the two walls. The blockhouses were then surrounded by barbed wire. After fortifying Tuglas the Royal Scots were ordered further upstream to the twin settlements of Borok and Seltso. But the Bolsheviks were starting to fight back. Their artillery outranged the Allies’ guns. The British gunboat returned to Archangel to avoid being trapped by ice when the Dvina was frozen by the coming winter. The Bolshevik gunboats continued to operate because the upper reaches of the river took longer the freeze over. Supported by the gunboats, elite Russian Marines, stalwarts of the Bolshevik revolution, attacked Borok. In mid-October the Allies decided it would be prudent to retreat north to the more easily defended settlement at Tuglas.

Disaster struck when around 120 Royal Scots were sent to attack the village of Topsa in a snow storm. Around 600 skilfully deployed Bolsheviks were waiting for them. The Royal Scots blundered into a web of well positioned Bolshevik machine guns and after being pinned down they were subjected to well organised flank attacks. Before they managed to retreat, the Royal Scots had suffered 26 dead and further 54 wounded or missing.

The Royal Scots were joined in the defence of Tuglas by American troops from the Detroit-based the 339th U.S. Infantry. The Americans held the south end of the settlement on the left bank of the Dvina. The Royal Scots and two 18-pounder guns crewed by the 67th Battery of the Canadian Field Artillery occupied the centre section of the settlement.

The Bolshevik attack came at around 8 a.m. on November 11th. Bolshevik gunboats emerged from the river mist to blast the block houses on shore. Then 500 Bolsheviks burst out of the forest and charged the Americans. The men of the 339th retreated, as planned, across the 18-foot wooden bridge which spanned a deep ravine which separated the southern part of the settlement from the central section. The Americans kept up a steady stream of rifle and machine-gun fire which held the Bolsheviks at bay.

The Bolsheviks also launched an attack on the Allied positions of the right bank of the Dvina but this was easily driven back by artillery and blockhouse-based machine-guns. Then, the Bolsheviks sprang their surprise. A force of 500 had marched through the forest to come out north of Tuglas. At around 9 a.m. they charged out of the trees at the Canadian 18-pounders. They would probably have over-run the guns if they hadn’t accompanied their emergence from the forest with a loud cheer. Canadian drivers, signallers and other non-gun crew snatched up their rifles and Lewis light machine-guns and attempted to hold up the Bolshevik charge. The unexpected and spirited response of the two dozen Canadians threw the Bolsheviks into disarray and their advance faltered.

Then, the Bolsheviks sprang their surprise. A force of 500 had marched through the forest to come out north of Tuglas. At around 9 a.m. they charged out of the trees at the Canadian 18-pounders. They would probably have over-run the guns if they hadn’t accompanied their emergence from the forest with a loud cheer. Canadian drivers, signallers and other non-gun crew snatched up their rifles and Lewis light machine-guns and attempted to hold up the Bolshevik charge. The unexpected and spirited response of the two dozen Canadians threw the Bolsheviks into disarray and their advance faltered.

An under-strength platoon of Royal Scots, possibly no more than 35 men, rushed to bolster the thin line of Canadians holding the Bolsheviks at bay. But the rush across the open ground to the Canadian positions cost them dearly. Most of the 15 Royal Scots killed that day died in the hail of bullets which greeted them as they strove to reach the Canadians. Many more were wounded; and four would die from their injuries in the days that followed. The Royal Scots accounted for half the Allied dead on November 11th.

Sergeant Christopher Salmons, from Essex, distinguished himself by charging into the Bolsheviks firing a Lewis gun from the hip. He was too obviously a target and was shot dead. Salmons had already been recognised for his bravery under fire when he rescued a wounded soldier a month earlier and also for organising a counter-attack when the column he was with was ambushed two weeks after that.

The Canadians managed to swing one of the 18-pounders around to face the Bolshevik attack from the north. Firing at almost point-blank range, the gunners helped the Royal Scots hold the Bolsheviks off. The fight turned into a stalemate. The Red Army could not advance in the face of the rifle, machine-gun and 18-pounder fire pouring from the Allied position. But the Royal Scots lacked the numbers to launch a full scale counter-attack and drive the Bolsheviks off. Bolshevik snipers had prevented the Canadians turning the second south-facing 18-pounder around until darkness fell. But once it was turned around the Bolsheviks pulled back. Only 100 Red Army men made it back to their own lines. A further 80 surrendered to Allied troops stationed further down river.

The Bolshevik gunboats returned next day and again on the 13th. Using ammunition which turned out to have been made in the U.S.A. they blasted five blockhouses at Tuglas to pieces. A raid on November 14th over-ran a blockhouse held by the Royal Scots. Lieutenant John Dalziell was captured in the raid and murdered. The battle for Tuglas, fought on the personal orders of Bolshevik leader Lenin, petered out when the Bolshevik gunboats withdrew upstream to avoid being trapped in the ice which was advancing south down the Dvina from Archangel.

The haul of Red Army prisoners taken at Tuglas included Latvians, Bulgarians, Germans and Austrians. One of the most interesting prisoners was dubbed Lady Olga. She had appeared dressed as a soldier when the Bolsheviks over-ran the Allied hospital at the north end of Tuglas. She stopped the Bolsheviks murdering the occupants and turned out to be the wife of the Bolshevik commander. Her wounded husband was treated at the hospital but died. She remained at the hospital after the Bolsheviks pulled back from Tuglas and became a prisoner.

The Royal Scots’ bravery at Tuglas did not go unrecognised: three Military Crosses, three Military Medals and two Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded to battalion members who took part in the battle. The Canadians netted one Military Cross, three Military Medals and three Distinguished Conduct Medals.

The Allies held Tuglas until the end of January 1919 and then burned the settlement before retreating 50 miles further down river.

Winter Gear

By then the Royal Scots had been kitted out with full winter warfare gear – sheepskin coats, leather jerkins, fur hats with earflaps, thick socks, sweaters and inner and outer gloves. The men were issued with special arctic boots made of canvas with thick rubber soles. The Shackleton boots were nowhere near as good as the knee-length felt boots worn by the local people. Sleighs were the standard mode of travel but some soldiers mastered the use of snowshoes and skis. Eventually, ski patrols were formed but they never succeeded in intercepting their Bolshevik counter-parts.

New blockhouses with improved protection from artillery shells were built. As winter tightened its grip on the Russian north heavy snowfalls meant the Royal Scots regularly had to leave the warmth of their blockhouses to dig their barbed wire out and haul back to the surface. In some places the snow was 10 feet deep. The men alternated between four days blockhouse duty and four days living in villagers’ homes.

The soldiers quickly found that touching metal with the bare hand was like grasping a piece of red-hot iron. And if a machine-gun jammed, the only way of getting it going again was to take it apart and boil it.

The work done to improve the blockhouses paid off when the ice broke up on the Dvina 10 days before it did at Archangel. The Bolshevik gunboats would have had free rein if the Allies had not managed to bring up some heavy artillery guns on Canadian designed sledges to support the Royal Scots.

The break-up of the ice and the re-opening of the Dvina to river traffic also meant the Royal Scots were no longer trapped in North Russia. The men, possibly influenced by the well-written English language Bolshevik newspaper The Call, had been asking why they were still fighting when most of the British Army had been disbanded months before.

The Commonwealth war memorials at Archangel list 88 men who died while serving with the Royal Scots – over 40% of total British casualties commemorated there.

Morale was raised when it was learned that two battalions of regular soldiers, including former officers who had re-enlisted as privates, were on their way to relieve the Royal Scots. By then several of the soldiers had found active service agreed with them so much that their medical category had been upgraded from B to A. But on the battalion’s return to Scotland many noted how weedy the heroes of the North Russian campaign looked. But few would disagree with the battalion’s commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel A P Skeil’s assessment of the Royal Scots as “triers”. He noted “Our experiences none of us would have cared to miss, but none would care to repeat”.

Photos Courtesy and Copyright of the Royal Scots Regimental Museum, Edinburgh Castle

Another article looks at the same battle but through a Canadian lens

Other articles you might be interested in -

*Here's one that combines Canadian and Scottish themes * Read about the blunder that made Canada an easy target for invasion from the United States - Undefended Border

* Read about the Second World War's Lord McHaw Haw

* Serious questionmarks over the official version of one the British Army's most dearly held legends - The Real Mackay?

* Read about the veterans of Wellington's Army lured into misery in the Canadian Wilderness in a new article called Pension Misery

* A sergeant steals the battalion payroll. It’s called Temptation

* Read about how the most Highland of the Highland regiments during the Second World War fared in the Canadian Rockies - Drug Store Commandos.

* January 2016 marked the centenary of Winston Churchill taking command of 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. How did the man who sacked so many British generals during the Second World War make out in his own most senior battlefield command? Find out by having a look at Churchill in the Trenches .

* Just weeks before the outbreak of the First World War one of Britain's most bitter enemies walked free from a Canadian jail - Dynamite Dillon

* Click to read - - Victoria's Royal Canadians - about one of the more unusual of the British regiments.

* This is one of the most popular articles on the site - Scotland’s Forgotten Regiments. Guess what it's about.

*********The 70th anniversary of one of the British Army’s most notorious massacres of civilians is coming up. See Batang Kali Revisited

A couple of years ago I saw an American “fly-on-the-wall” documentary series about life on a US aircraft carrier. This was after a US plane attacked a Canadian live-fire training exercise in Afghanistan and killed four of the men taking part. If the incident had happened a week earlier, there would have been five dead and I would have been the fifth man. I was horrified to learn that the pilot involved Maj. “Psycho” Schmidt had placed his 500 lb bomb exactly where I would have been standing if I’d been doing a newspaper story on the exercise – next to the anti-tank rocket launcher and the machine-gunners. I’d stood in that very spot while covering a daylight live-fire exercise and would have taken the same vantage point if I’d attended the night-time version. Luckily for me, the exercise was conducted a few days after I flew back to Canada.

But back to the documentary. The planes from the aircraft carrier were flying in support of US troops fighting in Iraq. The pilots’ frustration at never being called in to bomb or strafe anyone during their entire deployment was obvious. They wanted to do what millions of dollars had been spent training them to do. I wonder if “Psycho” suffered from the same frustration. I suspect he did. He and his supposed patrol commander were flying a similar mission to the pilots from the aircraft carrier – only over Afghanistan. I say “supposed commander” because the other pilot proved to have little control over “Psycho”. The pair spotted gunfire on the ground near the Kandahar airfield and the flash of what might have been an anti-aircraft missile being launched. The area near the base was often used for live-fire training exercises. The flash Psycho and his supposed commander saw was from the anti-tank rocket launcher being fired during the exercise. The men on ground didn’t even know Psycho and his buddy were high above them in the Afghan night sky until the bomb that ruined so many lives came whistling down. The two Air National Guard pilots were well above the range of machine gun fire or a shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missile. But for some reason they flew down towards what they thought was hostile fire. They radioed US control for information on who might be shooting – there was always a concern that the Bad Guys would infiltrate a night-fire exercise. Control had no immediate information about any exercise that night at the Tarnac Farm training area and advised the pilots to wait while a further check was done. But Psycho couldn’t wait. He killed four Canadian soldiers and maimed a couple more. Sadly, he was a very good pilot and an excellent aim. After the bomb was unleashed, one of the two pilots, I can’t remember which, said something along the lines of “I hope that was the right thing to do”.

Nope.

Psycho was no ordinary National Guard reservist. He was former regular and an instructor at the US Navy’s Top Gun training school. Both he and his buddy got what many regard as slaps on the wrist. Questions were raised about why US air control didn’t immediately identify the ground fire as coming from a Canadian exercise and the drugs issued to pilots to keep them alert during long standby patrols over Iraq and Afghanistan. Embarrassing questions which some people perhaps didn’t want answered or raised at a court-martial. Some plea bargaining was done. Psycho, probably on the advice of his lawyers, wouldn’t speak to the Canadian media. But his mother would. When, as a reporter on the Edmonton Sun, I asked her if her son had the slightest sliver, scintilla, of doubt about whether he should have dropped that bomb, she hung up on me. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. But apples seldom blow people to Kingdom Come.

It’s been several years since I first wrote about the 1948 Batang Kali Massacre in Malaya. Since then, there has been a resurgence in interest regarding the actions of the Scots Guards patrol which is reported to have shot around two dozen ethnic Chinese rubber plantation and tin mine workers in cold blood – while claiming the men died in a failed mass escape from questioning.

I thought when I wrote the incident up for my book Scottish Military Disasters that there was at least some agreement on the basic facts. But the various reports which have cropped up in the past couple of years show that there is little agreement on anything except the names of some of the patrol members and of some of the people living on the plantation.

I wrote that the patrol from G Company of the 2nd Scots Guards which raided the workers’ camp at Batang Kali looking for Communist guerrillas on 11th December consisted of 14 men. Now I find figures of 16 or 18 Guardsmen are being thrown around. But the figure of 14 is probably correct when it comes to Guardsmen. Most accounts agree there was a Malaya Special Constable and two ethnic-Chinese special branch detectives. One of the special branch men told Royal Malayan Police investigators in the early 1990s that he was not at Batang Kali but was not believed. Anyway, the three police officers bring the number of members of the security forces involved up to 17 and there may have been at least one Malayan guide involved.

Well, once you’ve worked out which regiment the old fellah was in, maybe you’d like to find out a bit more about his military service. Sadly, more than half of the service records, some say nearly two-thirds, were destroyed in a German bombing raid in 1940. But maybe you’ll be lucky. The National Archives at Kew holds the material which was not destroyed. Every soldier who fought in the war was entitled to at least one medal and the Medal Records can be found at the National Archives website and ancestry.com If the old fellah was killed, then the website Commonwealth War Graves Commission website may yield some information such as date of death, army number and unit, including which battalion was involved. The Scottish National War Memorial Roll of Honour can also be useful. Many local newspapers carried obituaries of men killed during the war and they might be worth checking at your local library. Some details of Pre-war regulars might be found at findmypast.co.uk. The folks at the Royal Highland Fusiliers Museum put together a list of services numbers for various Scottish regiments which were used for soldiers enlisting between 1920 and 1942;

Black Watch 2744001 - 2809000

Seaforth Highlanders 2809001 - 2865000

Gordon Highlanders 2865001 - 2921000

Cameron Highlanders 2921001 - 2966000

Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders 2966001 - 3044000

Royal Scots 3044001- 3122000

Royal Scots Fusiliers 3122001- 3178000

King's Own Scottish Borderers 3178001- 3233000

Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) 3233001- 3299000

Highland Light Infantry 3299001- 3377000

Records for military personnel from 1920 onwards, including the Second World War, are trickier due to privacy issues. These records are held by the Army Personnel Centre in Glasgow. They are only released to relatives - this requires the permission of the official next of kin. There is no charge to widows and widowers of the dead soldier for the information but all others have to pay £30.

Thanks to Ed Boyle and Alistair Cuthbert for this photo related to the Battle of Gully Ravine in 1915 (See Blooding the Pups in Scottish Military Disasters).

The photo is believed to have been taken at Grangemouth in May 1915, shortly before the 7th Battalion of the Scottish Rifles sailed for Turkey.

The young seated lad with the towel over his shoulder is Alistair’s great uncle Lieutenant Daniel Taylor. Can anyone identify the others? Alistair believes the four may be the platoon commanders from the battalion's B Company – that would make the others Lieutenants Duff, Brown and Maclay. None survived Gully Ravine. Two of the men do appear to be wearing officer-issue shirts with collars and the man with his hands in the pockets would seem to be wearing officer-style trousers.

Anyone with information can get in touch with through the “contact” feature on this site. Also, if you are unable to see the photo, I'd like to know.

Online

We have 67 guests and no members online